{:en}It was 1839 and a young German painter, Johann David Passavant, son of a provincial merchant, who had attended the school of Jacques-Louis David in Paris and then followed courses with the Nazarene mystics in Rome, decided to go to Urbino to discover something more about his favorite artist: Raphael, of whom he would later become a great and recognized expert.

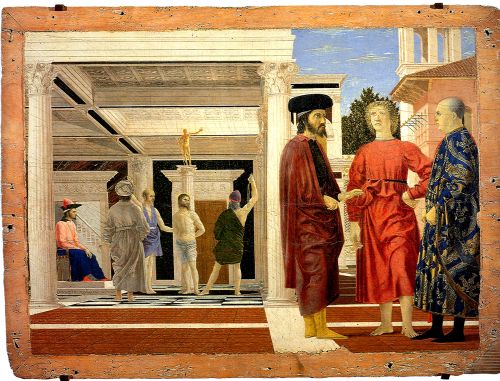

As often happens, when you look for one thing you always find another, Passavant by chance learns that Raphael's father had lived for a year with Piero de' Franceschi, the author of that small, semi-abandoned panel that he sees in the back of the sacristy of the Cathedral of Urbino and of this he says: “It represents Christ at the column in front of Pilate. In the foreground are seen three gentlemen, one of whom, richly dressed in silk and gold, is painted in the Dutch manner.

Today the panel of "The Flagellation" by Piero della Francesca can be admired in the National Museum of the Marche, in the setting of the splendid ducal palace of Urbino, one of the Italian architectural wonders. Piero di Burgo, as he was called, is self-taught, fellow citizen and friend of Luca Pacioli, the Franciscan mathematician author of the Divine Proportion, but also of other illustrious mathematicians and philosophers. He studies and applies the dictates of Pythagoras and Archimedes to achieve the perfection of his designs. He will also be called a painter and mathematician: his is the text "De prospectiva pingendi" where he writes a treatise on Albertian perspective and the "Libellus de quinque corporibus regularibus", an obstinate treatise on squaring the circle, an itinerary already followed by Nicholas of Cusa. He is not just a painter but an intellectual who studies space, an esoteric in search of the philosopher's stone.

An intriguing painter, therefore. Perhaps fifteen or twenty works of his remain and they are enough to make him a colossus of art history. Piero is the founder of a vision that remains intimately linked to his land, which extends between Tuscany, Umbria and Marche and ends in Urbino where one of his most important clients lived here: Federico da Montefeltro. He began his career here under the aegis of his patron, the prototype of the prince of the time: aggressive, alert, fighter, self-confident to the point that he was portrayed with the famous cut of the nose that allowed him to peek to the right with the only eye he had left. Piero and Federico are the emblem of the court of Urbino, so different from that of Florence, where there is only the power of money first and foremost and where you can have beautiful women. The Medici were highly cultured but even more cultured was Federico da Montefeltro with his library second only to that of the Vatican and who with his mercenary means - he was one of the most skilled leaders in the pay of the various potentates - earned very large sums which he reinvested all in his duchy. What remains in the Montefeltro land today is truly a masterpiece of architectural, pictorial, stylistic and artisanal skill.

But let's go back to scourging by Piero della Francesca, which is not just an enigma but a real puzzle.

Many art historians, as well as real policemen, using modern investigative techniques of face recognition, have given their version of the table, the unit of measurement of which is depicted in the black stripe you see above the head of the man with the pointed beard in the foreground, that is cm. 4,699. The table is seven times ten this unit.

The various interpretations try to symbolically explain who is hiding behind the actors present on the scene, who is Pilate sitting, or who is the man in brocade on the other side of the table but above all who represents the young blond man in the purple-red jacket - purple robes belonged only to kings, high prelates and emperors: obtaining this color was very expensive, cochineal was used, these poor little animals were not so easy to find - and with bare feet. Of some the recognition is clearer, the men with beards for example are Greeks, because in those times only they wore them. Even those who wear the turban are easily recognizable. About all the others, the most possible conjectures are unleashed, many of which are plausible, especially the most recent ones.

There are, even on the internet, different and compelling versions of the table and the characters depicted. For those who want to have a more in-depth idea of the period in which Piero lived, one of the most incredible and fascinating in our country, I recommend reading Silvia Ronchey's text, “The enigma of Piero”; leaves us surprised and with an irrepressible desire to know even more: about perspective, the divine proportion, the squaring of the circle and also about Leon Battista Alberti and his "De Re Architectura", philosophy in general and about Plato in particular, but even more on the history of the characters who lived in this extraordinary and fruitful period: Federico da Montefeltro, Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, Bessarion, the Palaeologus dynasty, Mistrà, Giorgio Gemisto Pletone, Byzantium, Venice, Carpaccio, Manutius, Marsilio Ficino, the Medici, Pius II, Cleopa Malatesta... the list would continue but I'll stop here.

It was an exciting period full of perspectives, where the countless Greek texts that were brought to Italy by fleeing exiles were consulted, copied and protected. Many of these ended up forming the basic heritage of magnificent libraries such as the Marciana in Venice and the Laurentiana in Florence.

It is difficult to summarize the meaning of this work in a few words without risking making it a real pseudo-fictionalized meatloaf which I leave to those who are more expert than me, I only reiterate that it would be worth working on this particular historical period and writing endless novels about it . One has the feeling that the content of his message, what the scholars of those times learned and deepened through the study of Greek texts, was barely mentioned, at least in Italy, and that for various reasons of state they then took different paths, away from here.

Leopardi, in my opinion, was one of those who later felt the void most.{:}{:en}

In 1839 a young German painter, Johann David Passavant, a provincial merchant's son who had attended Jacques-Louis David's school in Paris and then attended courses by the Nazarene mystics in Rome, moved to Urbino to discover something more about his favorite artist, whom later he would become a great and recognized expert: Raphael.

As often happens, when you look for something, you always discover something else, Passavant by chance finds out that Raffaello's father had lived a year together with Piero de' Franceschi, the author of that small, semi-abandoned table that you can barely see in the back of the sacristy of the Duomo of Urbino, and he tells that it “represents Christ at the Column in front of Pilate. In the foreground there are three gentlemen, one of them, dressed in silk and gold, is painted in the Dutch way”.

Today the painting “Flagellation of Christ” by Piero della Francesca can be admired in the National Museum of the Marche, in the frame of the splendid ducal palace of Urbino, one of the Italian architectural wonders. Piero di Burgo, as he was called, is a self-taught, fellow-citizen and friend of Luca Pacioli, the Franciscan mathematician author of the Divine Proportion, but also of other mathematicians and philosophers. He studies and applies the dictates of Pythagoras and Archimedes to achieve the perfection of his designs. He was later also called a painter and mathematician: he wrote the text “De prospectiva pingendi” where he draws up a treatise on the “Albertian perspective” and the “Libellus de quinque corporibus regularibus”, an obstinate treatise on quadrature of the circle, itinerary already run by Niccolò Cusano. He is not only a painter but an intellectual who studies space, an esoteric looking for philosopher's stone.

An intriguing painter, then. There are perhaps fifteen or twenty works of his own by him and are enough to make him a giant of the history of Arts. Piero is the founder of a vision that remains intimately tied to his land, extending between Tuscany, Umbria and Marche and stops at Urbino where one of his most important customers lives: Federico da Montefeltro. Here begins his career under the patronage of his patron, prototype of the prince of then: aggressive, awake, fighter, self-assured to the point that he is portrayed with his famous nose that allowed him to peek right with the only eye that he had remained. Piero and Federico are the emblem of the court of Urbino, so different from that of Florence, where there is only the power of money in the first place and where you can have beautiful women. The Medici are very cultured, but even more cultured is Federico da Montefeltro with his library second only to that of the Vatican and who with his mercenary means – he was one of the most skilled soldiers at the expense of the various potentates – earned very high sums that he reinvested all in his duchy. What remains in the land of Montefeltro today is truly a masterpiece of architectural, pictorial, stylistic, artisanship.

But let's go back to the “Flagellation” by Piero della Francesca, which is not just an enigma, it is a real puzzle.

Many Arts critics, as well as real police officers – using modern face recognition investigative techniques – have given their version of the painting, whose unit of measure is depicted in the black strip that you see above the head of the bearded man in the foreground, i.e. 4.699 cm. The painting is seven times this unit.

The various interpretations try to symbolically explain who is hiding behind the characters in the scene, who is Pilate sitting, or who is the man in brocade on the other side of the painting but above all who represents the young blond man with the purple scarf – the purple garments belonged only to kings, high priests and emperors: getting this color was very expensive, the coquette was used, these poor little animals were not so easy to find – and with their bare feet. Of some characters, recognition is easier, for example, bearded men are Greeks, because at that time they were the only ones wearing it. Even those wearing turbans are easily recognisable. On all others, the most likely guesses are made, of which many are plausible, especially the most recent ones.

There are also on the internet different and fascinating versions of the painting and its depicted characters. For those who want to have a more in-depth idea of Piero's life, one of the most incredible and fascinating of our country, I recommend reading Silvia Ronchey's text “L'enigma di Piero”. We are surprised and with an irrepressible desire to know even more: about perspective, the divine proportion, quadrature of the circle and again on Leon Battista Alberti and his “De Re Architectura”, philosophy in general and on Plato in particular but even more on the story of the characters who lived in this extraordinary and so fertile period (Federico da Montefeltro, Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, Bessarion, the dynasty Paleologus, Mistrà, Giorgio Gemisto Pletone, Byzantium, Venice, Carpaccio, Manutius, Marsilio Ficino, Medici, Pius II , Cleopa Malatesta … the list would be longer).

It was a time of excitement and full of perspectives, where the countless Greek texts that were brought to Italy by escaping exiles were consulted, copied, protected. Many of these ended up creating the basics of magnificent libraries such as Marciana in Venice and Laurentiana in Florence.

It is difficult to summarize in a few words the meaning of this work without risking of making it a true pseudo-fiction meatball that I leave to those who are more experienced than I am, I just repeat that it is worth working on this particular historical period and writing endless novels. It is felt that the contents of his message by him, as learned from the times learned by Greek scholars, has just been mentioned, at least in Italy, and that for various reasons have then taken different paths, far from here.

Leopardi, in my opinion, was one of those who later became aware of this void.{:}