When talking about Nicola di Maestro Antonio, one cannot ignore the fact that none of his works remained in the city where he was born.

Something is in Jesi and Urbino, in the National Gallery of the Marche, in the Vatican Museums, in La Spezia and in the Turin Museum. Everything else is found abroad: in Oxford, London, even overseas: Pittsburgh, New York, Baltimore.

And to think that most of the tables all came from one place: the Church of San Francesco alle Scale in Ancona. It makes me cry just thinking about it.

And "grieving the loss of a work of art is no different from mourning a man", states Umberto Galimberti.

Asking too many questions is sometimes not good and touches exposed nerves: Ancona has always had its own way of dealing with culture in general – Ciriaco Pizzecolli's grandfather described the city like this:

totam non liberalbus studiis sed mercemoniis dedicated (wholly dedicated not to liberal studies, but to commerce) - but perhaps it would be time for the competent authorities to organize an exhibition that brings together all the works of this extraordinary painter so as to make him known to the people of Ancona and beyond.

EH Gombrich says: "after all, art doesn't exist, artists exist, and you can ruin an artist by claiming that his work is excellent in its own way but it's not about art, after all, but about something else."

Or you can do something much worse: forget the artist, carry out a real repression.

What do we know about him and his life? Little or nothing. He is the son of Antonio di Domenico di Neri di Lapino, also a painter, who emigrated to Ancona as did numerous Florentine exiles, some truly illustrious, such as Felice Brancacci, Masaccio's client in Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence and Rinaldo degli Albizi, one of the most powerful men of the anti-Medici faction in the first decades of the fifteenth century. Nicola was born between 1445 and 1450 and mention began to be made of him around 1465, with his pictorial parable which begins with the Ferretti Altarpiece.

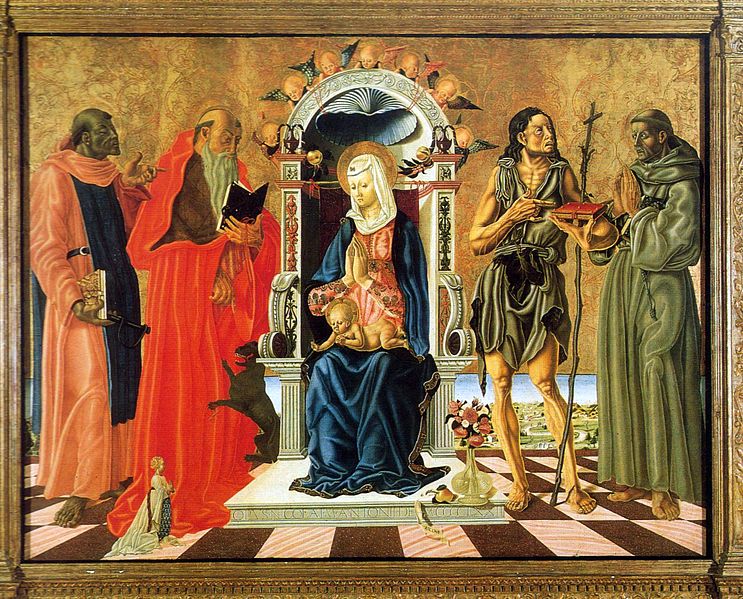

What is striking is the harmony of the painting and at the same time a disharmony of elements in apparent contradiction with each other: the checkered floor and the canopy, the vase of flowers and the fly, the countryside background and the panel with the embroidered raceme in the middle, not to mention the four saints with John with the suffering face, the sharp contours and the naked, deformed legs of a survivor of the Apocalypse. Francesco and Leonardo dark-faced. An alchemy of elements and figures, characters who play the race of life like in a game of chess, in the search for a higher degree of knowledge (book) which illuminates man and makes him divine.

Antonio is a child of his time, he is prospective and icastic, he takes inspiration from Piero della Francesca, who among other things seems to have also lived in Ancona and from Crivelli.

Another masterpiece is the Massimo Altarpiece followed by the predella where Saint John the Beheaded and Saint Lawrence, the Annunciation, Saint Anthony and the lunette of the risen Christ are depicted. Wonderful composition of characters and scenes, such as that of the stoning of Saint Stephen.

Ancona in the Renaissance was a crossroads of important figures, from Pope Enea Piccolomini, to the passage of the last line of Byzantine emperors, from Ciriaco Pizzecolli to Piero della Francesca, not to mention artists such as Giorgio da Sebenico and Giovanni Dalmata.

A city that has always been suspended between Venice and the Levant, between the Apennines and the Adriatic.

And Nicola di Maestro Antonio's brush was an added element of great artistic and cultural depth.