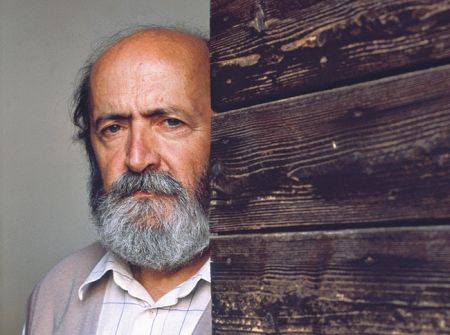

Sul monastero di Montebello e Gino Girolomoni gira una leggenda, misteriosa e seducente, che aderisce perfettamente alla figura mistica dell’ uomo che ho avuto il previlegio di conoscere. Si narra che quando Gino vide per la prima volta il monastero , abbandonato e invaso dai rovi, fu colto da un visione: dal bosco adiacente l’ edificio gli apparve un carro , un carro di fuoco , un immagine che richiama simboli biblici , e lui, uomo profondamente religioso, lo percepi’ come un presagio, un messaggio divino cui prestar fede: doveva far ritornare alla vita l’ antico monastero.

Non doveva essere stato facile per lui, di modestissime origini contadine, senza madre e con un padre malato affrontare la sua giovane vita, glielo si leggeva ancora negli occhi di adulto, ma era sempre stato un tipo determinato oltreche’ intelligente, sentiva che il mondo stava cambiando e si chiedeva continuamente come e in che modo e che cosa avrebbe potuto fare per mantenerlo il piu’ possibile intatto, altrimenti quei cambiamenti avrebbero per sempre stravolto lui e i suoi amati luoghi , le campagne e quella vita dove la vita aveva sempre avuto un senso. ” La natura stava gridando” mi disse una volta ” e io fui l’ unico ad ascoltarla” E fu’ cosi’ che comincio’: con i i giovani di Isola del Piano a formare una comune agricola, a lavorar la terra e le stalle con le vacche vere. ” ricordo soprattutto il freddo dell’ inverno” mi disse una giorno uno di loro, Peppino Paolini, oggi sindaco di Isola del Piano, mostrandomi delle foto in bianco e nero: lui e Gino con un metro di neve e la pala in mano accanto al monastero. Gia’, non deve esser stato facile,e difatti la comune falli’ e ognuno prese la sua strada ma Gino rimase, fermo nel suo progetto con la Tullia, sua moglie, che gli rimase accanto e gli diede tre figli, e quindi il monastero, la locanda, il pastificio, la cooperativa e il suo messaggio di un agricoltura senza pesticidi e conseguentemente di un cibo piu’ sano , tutto riunito in un unico simbolo: Alce Nero . Ma chi era Alce Nero e che cosa significava per Girolomoni? Credo che significasse molte cose insieme : il guerriero Sioux che resiste, resiste all’ invasione occidentale, resiste in nome della natura , il guerriero che sin da piccolo ha delle visioni e le racconta, il guerriero che si converte al cattolicesimo pur mantenendo le proprie tradizioni , guerriero infine che racconta ( Alce Nero parla ) perche’ il suo grido non si disperda nel vento. Gino Girolomoni era Alce Nero.

Autodidatta, studiava e leggeva continuamente . All’ epoca diventa saggista, collabora con diversi giornali, scrive libri e fonda una rivista ” Mediterraneo” , oltre a presiedere la fondazione Alce Nero, intesse importanti relazioni con intellettuali e politici del suo tempo: Sergio Quinzio, Guido Ceronetti, Paolo Volponi, Marina Salamon, Massimo Cacciari, Moni Ovadia, Andrea De Carlo. Sono solo alcuni dei nomi che sono stati suo ospiti al Monastero e hanno parlato in una delle sue tante conferenze che attiravano tante belle menti da tutto il paese e da tutta Europa.

Nel frattempo il monastero, restaurato nell’ arco di quarant’ anni, viene completato con il recupero della chiesetta, e ancora oggi e’ possibile ammirarlo al suo interno in quanto sede del museo della civilta’ contadina. Gino aveva finalmente realizzato la sua visione: un’ opera straordinaria se solo poteste vedere la grandezza dell’ edificio che vi invito a visitare, sopra le colline di Isola del Piano, sull’ altopiano delle Cesane che vede il mare e la strada che porta ad Urbino, cui dista solo una decina di chilometri, per una strada bellissima e aperta, perche’ alta e panoramica , attorniata dai boschi di conifere e querce, che appartengono fortunatamente al demanio.

Qui uno stralcio di un suo intervento del Luglio 1973 in un convegno a a Isola del Piano, al quale avevano partecipato molti intellettuali. Sentite cosa accadeva una volta, non moltissimo tempo fa, nelle campagne marchigiane.

” queste pagine sono state scritte da uno che ha rovesciato la terra con l’ aratro trascinato dai buoi e che lo fa oggi con il trattore, da uno che ha abbattuto il fieno con la falce e che oggi lo fa con il motore. Uno quindi che ne conosce bene la differenza. Alla fine degli anni cinquanta la popolazione della campagna di Isola del Piano viveva ancora come nei secoli passati, unica differenza erano le trebbiatrici del grano e la lieta conseguenza che ne derivava: invece del pane di ghianda come agli inzi del secolo, si mangiava quello di grano. La televisione non c’ era ancora e neanche il frigorifero e la lavatrice. Non c’era l’ automobile e nemmeno il trattore. E non c’ era ancora la plastica , i recipienti per la cantina erano di legno e quelli per il bestiame in ferro. Non c’ erano le strade attraverso le quali queste cose potessero arrivare.

Nelle case venivano ogni tanto solo il povero Secondino, con la cavalla che mordeva, a vendere il sapone e la conserva e prendere in cambio le uova , e veniva Cimicia a comprare le pelli di lepre e di coniglio. Una volta all’ anno veniva Baffone a vendere i pettini , i rasoi, gli organetti e ogni volta che veniva mi prendeva voglia di suonarlo mentre mio nonno mi faceva invece lo zufolo di canna. Poi, una volta all’ anno, passava l’ arrotino ad arrotare e lo spranghino a sprangare i cocci che si erano rotti. A marzo veniva Din Din con l’ alambicco per fare la grappa con le vinacce e dormiva nella stalla.

La mancanza di strade maestre provocava molte difficolta’ ad esempio la levatrice o il medico bisognava andarli a prendere con la slitta o il biroccio trainati dai buoi, la domenica si vedeva la gente scendere dalle colline con le scarpe in mano da cambiare prima di entrare in paese. Non c’ era acqua corrente e e non c’ era energia elettrica e l’ illuminazione si otteneva con i lumi a petrolio e con la centilena.

Sempre negli anni cinquanta i contadini dicevano che se avessero avuto l’ acqua, la luce e la strada allora si che lla loro condizione sarebbe stata piu’ sopportabile. Dalla fine degli anni cinquanta e’ arrivata la strada, poi la luce e poi l’ acqua ma la gente dei campi se n’ e’ andata ugualmente. Perche’? Perche’ la gente in quegli anni fu’ colpita da una grave malattia , quella di porsi le domande ( prima le domande se le ponevano soltanto i ricchi, mentre il popolo lavorava) Perche’ devo dare la meta’ al proprietario? perche’ non posso far studiare i miei figli? Perche’ ‘ non posso avere una casa comoda e pulita? Perche’ quando vado in citta’ negli uffici mi guardano con disprezzo e non mi ascoltano neanche? Dopo essersi posto queste domande se ne sono andati lungo la Flaminia tra Fossombrone e Fano e lungo l’ Adriatica a verniciare mobili di legno sintetico o a fare i manovali.Ma anche molti contadini che possedevano i campi che lavoravano se ne sono andati e quindi che cosa ha determinato la fuga dalla terra dunque? I figli che in citta’ hanno fatto un po’ di scuola , la moglie che qualche volta ha visto la citta’ ne e’ stata sedotta e ha convinto il marito a farsi la casa nelle monotone e sterminate periferie’. E cosi’ uno lascia la sua terra, le tradizioni, gli amici illudendosi che basti un maggiore guadagno e i servizi della citta vicina per compensare quello che perde lasciando i campi che erano del padre e del padre del padre e dove tutti sapevano chi era e come si chiamava mentre dove va nessuno sa chi e’. Con la strada e’ arrivata la motocicletta e poi la lavatrice e il frigorifero, poi il trattore, la motofalce a benzina, e cosi’ tante querce sono state abbattute mentre prima si faceva fatica a tagliarle e le si lasciava li’.

Oggi la quantita’ della produzione agricola e’ aumentata ma non la qualita’ , a causa dei fertilizzanti artificiali e dei diserbanti. Anche la qualita’ della salute ha subito un danno notevole, non c’ e piu’ di un coltivatore che non abbia una malattia per la quale, se non cresce presto il figlio, non puo’ piu’ mandare avanti il campo. La polvere dei concimi e degli erbicidi che ha respirato e’ stata dannosissima ma anche la salute della terra e’ destinata a crollare: due anni fa in Olanda mi sono fermato a vedere un campo di grano e ho toccato la terra e la spiga piccola e malata, la terra non sembrava piu’ terra ma un prodotto sintetico. E che dire delle nostre piante da frutto che non fanno piu’ frutti se non sono ripetutamente trattate? Ormai l’ equilibrio ecologico della natura si e’ rotto e solo la natura , in un modo forse disastroso per gli uomini, puo’ ristabilirlo.

Prima il combustibile veniva dal campo vicino a casa ed era il fieno e l’ erba, adesso viene dall’ Arabia Saudita. A casa le donne facevano la pasta e il pane, il forno andava a legna e la legna non costava niente. Non solo, dalla molitura del grano usciva anche il cibo per i maiali, la crusca. Prima che non c’erano le macchine c’ era anche il tempo di fare il pane, adesso che ci sono i trattori e l’automobile quel tempo non ce l’ hanno piu’ . Il mio discorso non vuole sostenere niente, dico che qualcosa non funziona: adesso che in campagna ci sono i trattori con tutti gli accessori i contadini lavorano lo stesso numero di ore di quando c’erano le mucche. E di soldi in tasca gliene rimangono quanti ne rimanevano prima. E allora? E allora c’ e’ qualcosa che non funziona, cioe’ non funziona niente!

Una grande civilta’ e’ praticamente scomparsa: gli aratri di legno, i telai per tessere la lana, le pietre lavorate per stendere i bachi da seta, la pialla gigantesca per fare i tini e le botti, ogni famiglia produceva canapa e lana e seta e le lavorava, dal legno del bosco si ricavava una sedia, una botte e un recipiente. Ogni famiglia era autosufficiente.

Il molino di pietra e’ dell’ ultimo scalpellino che c’ e’ rimasto a Isola, le pistole per i portoni sono dell’ unico fabbro, le sedie e le scarpe e i cesti e i canestri, passata la generazione di mio padre non li sapra’ fare piu’ nessuno.

Se e ‘ vero che indietro non si torna e’ vero anche che avanti c’ e’ il caos. Se la gente sapra’ fare anche queste cose potra’ sopravvivere. Io me lo auguro e cerco d’ imparare a farle. ”

” Sulle tracce dei nostri padri” – Anno 2000, Fondazione Alce Nero

Tutto questo lo scriveva nel 1973

Le sue parole , davvero profetiche, forse avrebbero meritato una maggiore riflessione. Se poi pensiamo alla crisi dei nostri tempi, alle nostre fabbriche che chiudono e l’ avvento della Cina con altra distruzione della natura che si ribella creando disastri ecologici di portata mai vista prima, forse penso che la fuga dalla terra sia stata un grosso errore, proprio come diceva Gino.

{:}{:en}

There is a legend about the Monastery of Montebello and Gino Girolomoni. This legend is mysterious, seductive and perfectly reflects the mystical figure of the man I had the privilege of meeting. Gino had a vision when he saw for the first time the monastery, which had been abandoned and invaded by the trenches. A chariot, in particular a fire chariot, appeared in the woods adjacent to the building. This is an image that recalls biblical symbols, and because of his profound religiousness, he interpreted these symbols as a divination, a divine message indeed, to which he relied that the monastery had to be brought back to life.

His youth was certainly not easy, he had modest and peasant origins, with no mother and with a sick father. You could read it in his adult eyes. However he had always been a resolute although smart type, he felt that the world was changing and he was constantly wondering how it would change and what he could do to keep it as intact as possible. He believed that those changes could overturn him and his beloved places, the country-sides and everyday life where everything was meaningful.

“Nature was shouting,” he told me, “and I was the only one to listen to her.”

That was how he formed with the young people of Isola del Piano a community farm, working the land and managing stables with real cows.

“I remember especially the cold of winter” one of them said to me – it was Peppino Paolini, recently mayor of the Island of the Piano – showing me some black and white pictures: Peppino and Gino under a meter of snow and the shovels next to the monastery.

It was certainly not easy, and in fact the community failed and everyone left, but Gino remained. He remained deeply convinced of his own project, together with Tullia (his wife), who remained next to him and gave him three children, and then the monastery, the inn, the pasta factory, the co-operative and the message of a pesticide-free agriculture and consequently of healthier food. All gathered in a single symbol: Alce Nero.

What was Alce Nero and what represented for Mr. Girolomoni? I believe that it meant several things altogether. A Sioux warrior who resists, resists to Western civilization, resists in the name of nature; a warrior who has a vision and tells everyone about it, the warrior who converts to Catholicism while maintaining his traditions, the warrior who tells stories (i.e. Alce Nero speaks) so that his screams do not disappear in the wind. Gino Girolomoni was Alce Nero.

Self-taught, studied and read continuously. At the time he became an essayist, collaborated with several newspapers, wrote books and established a magazine “Mediterraneo”, in addition to chairing the Alce Nero foundation, kept relations with intellectuals and politicians of his time: Sergio Quinzio, Guido Ceronetti, Paolo Volponi, Marina Salamon, Massimo Cacciari, Moni Ovadia, Andrea De Carlo. These are just some of the names that were his guests at the Monastery and have spoken in one of his many conferences that attracted many beautiful minds from all over the country and from Europe.

Meanwhile, the monastery was restored over forty years, and it is finally completed with the restoration of the church. Still today it is possible to admire it since it hosts the museum of peasant civilization. Gino had finally turned his vision into reality: an extraordinary work, if you could only see the greatness of the building that I invite you to visit, upon the hills of Isola del Piano, on the plateau of the Cesane overlooking the sea and the road leading to Urbino (which is only a dozen kilometers away), through a beautiful and open road, because it is high and panoramic, surrounded by coniferous woods and oaks, which fortunately belong to the public property.

Below is an excerpt of a speech of July 1973 at a conference at Isola del Piano, to which many intellectuals participated. Here’s what was happening not so long ago in the countryside of the region Marche:

“These pages were written by one who overthrew the ground with the plow dragged by the oxen and that it does today with the tractor, one who has dropped the hay with the sickle and that it does today with the engine. One who therefore knows the difference too well. At the end of the 1950s, the population of the countryside of Isola di Piano still lived as in the past centuries, the only difference was wheat threshing machines and the delightful consequence that resulted from it: instead of the acorn bread at the beginning of the century, now you had wheat bread. Television was not even there and neither the fridge nor the washing machine. There was no car or tractor. And there was still no plastic, the basin containers were made of wood and those for iron cattle. There were no roads through which these things could come.

Only the “poor” Mr. Secondino was visiting home, with his biting mare, selling soap and preserves and taking the eggs in return, and Cimicia came to buy hare and rabbit skins. Once a year, Baffone came to sell the combs, shavings, and orgies, and whenever it came to me, I wanted to play it while my grandfather used to do the cane bush. Then, once a year, the knife grinder would visit home and then the person who could bring the broken crocks. In March came Din Din with the almond to produce Grappa from the marc and slept in the stable.

The lack of main roads caused many difficulties, for example, you had to fetch the midwife or doctor by sled or by cart carried by oxen, on Sunday you could see people coming down from the hills with the shoes in their hands they would wear before entering the village. There was no running water and there was no electrical power and the lighting was obtained with the oil lamps and the centilene.

Still in the 1950’s, peasants said that if they had had the water, the light and the road then their condition would be more bearable. Since the end of the 1950s the road has come, then the light and then the water but the people of the fields have gone anyway. Why? Because people in those years were affected by a serious illness, the illness of asking questions (only rich people had questions before, while peasants had no time for questions since they had to work) Why should I give half of my earnings to the land owner? Why can’t my children study? Why can’t I have a comfortable and clean home? Why then, when I go to town in the offices, I am looked at in scorn and nobody would ever listen to me either? After asking themselves these questions, they went along the Flaminia road between Fossombrone and Fano and along the Adriatic road to paint synthetic wood furniture or to become manual laborers.

But also many peasants who owned the fields they worked had gone and so what is that caused the escape from the countryside then? The children who have been in school somehow, the wife who has sometimes seen the city has been seduced and has convinced her husband to get home in the monotone and exterminate suburbs. And so you leave your land, your traditions, your friends thinking that you need a better income and services of the nearby city to compensate what you lose from leaving the fields that were your father’s and your father’s dad and where everyone knows who you are and what’s your name wherever you go, while nobody knows who you are. By the way the motorcycle came and then the washing machine and refrigerator, then the tractor, the gasoline motoffs, and so many oaks were cut down before it was hard to cut them and left them there.

Today, the amount of agricultural production has increased but not the quality due to artificial fertilizers and herbicides. Health quality has also suffered greatly, there is no more than a farmer who has no illness for which, if he does not grow up soon, he can no longer carry the field. The fertilizer and herbicide dust that has been breathing has been very damaging, but the health of the earth is going to collapse: two years ago in Holland I stopped to see a field of grain and touched the ground and the small, sick ear, the earth seemed no longer earth but a synthetic product. And what about our fruit plants that no longer fruit unless they are repeatedly treated? By now the ecological balance of nature has broken and only nature, in a way disastrous for men, can restore it.

The fuel used to come from the field near home and it was hay and grass, now it comes from Saudi Arabia. At home the women made pasta and bread, the oven was fueled by wood and the wood did not cost anything. You could have bran for feeding pigs from the grinding of wheat. Before the machines were there, there was also time to make bread, now that there are tractors and the car that time no longer has them. My speech does not want to say anything, I only say that something is not working properly: now that there are tractors in the countryside with all the accessories, the peasants work the same number of hours as if there were cows. And the money in their pockets remains as much as before. And so? Then there is something that is not working, or maybe, nothing actually works!

A great civilization has practically disappeared: wooden plows, woolen weaving looms, stones worked to wrap silkworms, the giant plateau to make quails and barrels, each family produced hemp and wool and silk, and he worked, from the wood of the wood a chair, a drum and a bowl were made. Each family was self-sufficient.

The stone mill is the last stone-stone left in Isola, the guns for the gates are the only blacksmith, the chairs and the shoes, and the baskets and the baskets, my father’s generation is gone, will not know how to do any more.

If it is true that back is not back it is also true that there is chaos ahead. If people know how to do these things, they will survive. I wish him and I try to learn how to do it.”

“Sulle tracce dei nostri padri (On the footsteps of our fathers)”, Published by Foundation Alce Nero, 2000.

This was written in 1973.

His words are prophetic: maybe they deserved much more reflection. If we think about our times decay, about closing factories and the development of China helping destruction of nature, that reacts with never seen before ecological disasters, I believe that perhaps the escape from the countryside was a big mistake, just like Gino used to say.

{:}